BRI contributes to global peace and development, offers prospect of a better world: European expert

Since its very inception, China has made it clear that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a global public good that aims to promote mutual understanding and build a community of shared future for mankind.

The BRI embodies an attempt to construct a peaceful world, as well as to promote development, lift people out of poverty and improve their lives, Michael Dunford, Emeritus Professor at University of Sussex, told the Belt and Road Portal (BRP) in a recent interview.

Michael Dunford is currently working as a visiting professor at the Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. In the interview, he shared his thoughts on the significance and potential of the BRI to contribute to global development and his suggestions on countering the existing challenges in future development.

BRP: With your years of experience living and working in China, how would you describe your impression of this country?

Michael Dunford: I was swept off my feet by China when I first came in 2006 attending a high level seminar on comparative regional policy. I was amazed by the life conditions of ordinary people, compared with what I had seen in other developing countries I had been to.

From 2008 to 2012, I was involved in three joint projects involving German International Cooperation and the State Council Leading Group for Poverty Alleviation and Development: economic reconstruction after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, livelihood reconstruction after the 2010 Yushu earthquake and the 2010-2020 national poverty alleviation pilot in the Wuling Mountain Area, as a result of which I saw how China was addressing rural poverty.

In 2009, a friend working at the IGSNRR asked me to apply for a visiting professorship. So I applied three times and got three awards, which enabled me to come to China for six months a year from 2010 to 2015. After that, I was able to work part-time or full-time at the IGSNRR, enabling me to stay in China to this day.

Through these years, what surprised me was the speed of change. As I live in Beijing, sometimes it is almost as if the city was changing in front of my eyes. Especially, what seems really remarkable is the transformation of the quality of environment in Beijing.

Another thing that struck me is how, in recent years, one can visibly see quite extraordinary changes in China’s direction of development toward a people-oriented and common prosperity path, as opposed to focusing mainly on GDP growth. Much more attention is paid to the improvement in the quality of people’s lives and also the ways in which these improvements get down to the people who need them most.

BRP: How did you become interested in the BRI?

Michael Dunford: I think the BRI offers the prospect of a better world.

To me, one of the most important things about the initiative is the fact that the founding principles are in line with the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, which are extraordinary principles on which the world ought to be founded.

We live in a world where too many people’s lives are disrupted by war and too many countries are destroyed by war, which means it is essential to find a new way of dealing with conflicts.

The BRI embodies such an attempt to construct a peaceful world, promote development, lift people out of poverty and improve their lives through development. Obviously it is not just the responsibility of China. If China cooperates with a country, the country itself has a responsibility to ensure that the benefits spread deep down into its own society.

BRP: Your research field covers global development. Do you see potential in the BRI to promote equitable global development?

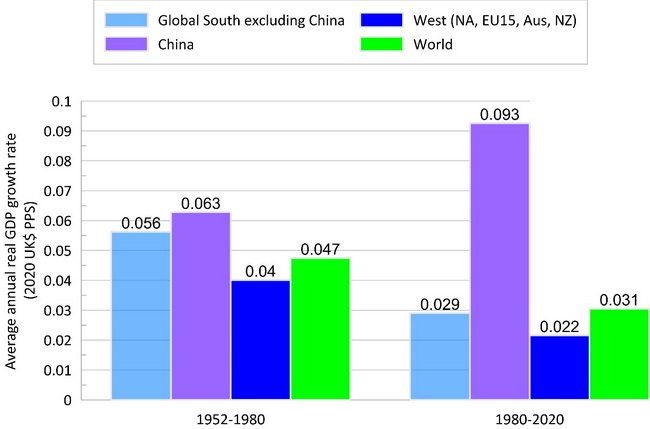

Michael Dunford: I made this chart to demonstrate the argument of my answer to your question.

As is shown in the chart, the average annual real GDP growth rate of the world is in green. In dark blue is, what I call, the West, which includes North America, the EU 15, Australia and New Zealand. Then I separated out China in purple because China’s record is quite distinctive. And in light blue is the record of the Global South excluding China, which is basically the rest of the world excluding the West and China.

From 1952 to1980, both China (in purple) and the Global South excluding China (in light blue) grew faster than the world average (in green), which means that generally speaking, the rest of the world started to catch up – they developed faster than the developed world and the inequalities in the world got smaller, even though the West saw strong rates of growth at 4 percent per year.

But then, after 1980, the situation changed significantly, in which the Volcker Shock and the debt crisis that followed played a critical role. From 1980 to 2020, the overall growth of the world economy was slower than it had been in the previous 30 years, and the growth rate of the Global South excluding China became less than the world average, which means they were, in a sense, left behind.

It was the era of Washington Consensus policies. Under that policy regime, the record of different countries varies. Many African countries had growth rates of only 1 percent per year or even less. In Latin America, the 1980s was a "lost decade", while South Asia grew at about 4 percent per year on average.

But if you look at China, China grew at more than 9 percent per year throughout that period. In fact, from 1980 to 2018, China’s real GDP per capita had increased 22.5 times. Given this extraordinary record, one needs to look at how China developed. Obviously, the way China developed is in part a result of China’s social and economic model, and there are economic aspects of that model which are quite distinct from the Washington Consensus model – it is centered on investment in infrastructure.

If a country invests in infrastructure, its logistic costs and transport costs will be reduced. It can then invest in industries, create employment and start to raise incomes. As industries develop, a country will start to generate exports, which can be used to acquire capital goods (more cheaply as a result of infrastructure improvements) and further upgrade the industries, while the growth in income will expand the domestic market. To some extent, I think that these ideas are embodied in the BRI, which means the BRI can make a significant contribution to the development of developing countries and thereby narrow the global development gap and accelerate global development. Obviously, it depends upon other things, such as the competence of government, the management of economic change, investment in skills and education to upgrade the workforce and so on – these are things that other countries have the capacity to do, especially if they have access to capital resources and preferential loans. And if other countries develop, China’s own markets will expand.

In this sense, the BRI is important not only because it can contribute to peace, but because it can contribute to equitable global development in a way that has been demonstrated historically to work by China’s own experience and in a way that the Washington Consensus model demonstrably failed to do.

BRP: How would you evaluate the scope and future potential of China-Europe cooperation under the BRI?

Michael Dunford: There is clearly considerable scope to cooperate in terms of infrastructure investment between Europe and China, and infrastructure that reduces logistic costs can generate remarkable gains for both sides.

There are a number of projects that have been extremely successful, if you think about the development of the Port of Piraeus in Greece, whose growth has been very strong in the last five or six years, as well as the railway project initially from Southwest China’s Chongqing Municipality to Germany’s Duisburg, which was widely copied later on. In the pandemic, the China-Europe freight trains proved extraordinarily important because it was one of the most important ways for moving medical supplies to Europe.

BRP: What are the challenges and difficulties in promoting China-Europe cooperation?

Michael Dunford: Part of the difficulties derive from the rules that the EU seeks to impose on other countries, which are not reasonable because the competitiveness of enterprises in less and more developed areas differs.

In a situation where a developing country is opening up to an extremely competitive part of the world, there is a chance that the industrial capacity of the developing country could be severely damaged due to its lack of competitive advantage.

Even with Western development itself, the West could not meet its own current standards 50 years ago, and even less so 150 years ago when it was at the start of its development process. Therefore, rather than simply impose European rules on China, the EU and China should manage their relationship and come to agreements and mechanisms whereby both sides gain. Of course, present-day China is not the China of 20 or 40 years ago: its industries are more competitive and it is able to compete on more equal terms and with fairer results.

If you look at what China did, China managed its opening-up. It did not open the whole country overnight. It initially established four special economic zones, which gave Chinese industries and enterprises time to adjust to the arrival of new competition. It also established joint ventures so that China could learn: the diffusion of knowledge plays a very important role in human progress, and, while one may want to repay the labour of innovators, it is important not otherwise to limit the diffusion of knowledge. So my view is that opening-up must be managed in ways where you can make sure that the gains are shared, that knowledge diffuses, which is what China has done.

BRP: As the BRI moves forward, voices that undermine and question it have also emerged. What do you think about these?

Michael Dunford: First of all, I think when the West looks at China, it looks at it through Western eyes. It has this view that great power rivalry and zero-sum politics is an inevitable and unavoidable feature of the relationships between countries and it thinks China is no exception. Western countries have sought hegemony, they think China will seek hegemony.

But the thing is, western theories do not explain China.

For example, I was struck about the story of Zheng He, an ancient Chinese navigator during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). In seven voyages, he did not colonize anywhere – all he did was try to demonstrate to the world the magnificence of his country. Whereas when Chinese inventions such as gunpowder, the magnetic compass and watertight compartments in ships reached Europe across the Silk Roads, what the Europeans did was, in the words of the Italian economic historian Carlo Cipolla, put guns on ships and conquered the world.

Another problem is that media, in a certain sense, looks for bad news. Early on, I met a German journalist and I asked why there is no good news about China in his newspaper? His reply was: if you want to read good news, read the travel section.

If you live in the West, you quickly realize that newspapers and the media are full of bad news. But you know that what happened affected only a few people and is not the general state of affairs. You can put what you see and hear in the context of your own daily life and you know it is not representative. But if it is all you hear or read about countries thousands of miles away like China, and if you have no personal experience and no way of contextualizing it, you may be led to think that it is common, unless of course you have been there. And in fact, people who have actually been to China generally have very positive views of China because they can contextualize what they read and hear in western media. If the BRI encourages more people to people exchanges it will help address this problem.

BRP: Do you have any suggestions on how to counter such critics and misrepresentations?

Michael Dunford: I think it is really interesting and important to think about building narratives around the BRI projects in the host countries – building links with local communities and local media, providing information, getting school children to visit the projects and be told about them and so on.

I also think that one should look at projects as processes that unfold, that encounter challenges, that involve a quest for solutions and that involve benefits that are not confined to individual projects but also their wider repercussions. For this reason I think that repeat studies, studies of wider impacts and articles and reports to deal with the way projects evolve and problems are solved are very important.

In this way, one can do an enormous number of positive things in terms of not only generating goodwill, but also letting people understand, see the positive side of what is going on and see how solutions are found if problems arise. This is a really important counterweight, because it is easy to misrepresent if people cannot put things in context. But if they have a different experience through these activities, they have now got a context in which they can situate other things they might see and hear.

BRP: Could you share with us some of your thoughts on the future efforts to promote high-quality development of BRI?

Michael Dunford: To me, the priority is to move toward an emerging world that is more unified and peaceful. This is linked with precisely what China has been saying – the BRI is open to anyone to join and is a road to peace. So in the future, I think it is essential to continue to make sure that the BRI is inclusive and that all regions and countries cooperating under the BRI are valued.

That being said, you still cannot make an omelette without breaking eggs. This means that in any development there can be people whose lives are disrupted in one way or another. In this sense, high-quality development means equitable development, development that contributes to common prosperity and seeks to make some people better off and no one worse off. It means that attention must be paid to the compensation of people whose lives are disrupted.

And I think there are other dimensions of high-quality development. Development should be productive in the sense of focusing on real economic activities. It should be clean, which means the avoidance of corruption of all kinds. And it should be green, which means the planning, implementation and operation of projects are associated with adequate levels of environmental protection and enhancement.

In addition, I think high-quality development also means development that embodies modern advanced technologies, a point which is reflected in the promotion of the Health Silk Road and the Digital Silk Road. Humanity is on the verge of a new industrial revolution in fields like biotechnology, artificial intelligence, robotics, 5G technologies, quantum computing and beyond. These technologies offer huge potential for increasing productivity and improving the quality of life.